On the 29th March 2019, the United Kingdom is (currently) scheduled to exit the European Union. To celebrate forty-six years of peacetime and prosperity in Europe, this season we’ll be profiling the footballing history of each remaining member of the EU, looking at some of their most iconic matches and the players that have left a lasting impression on the game. It’s back to the Lowlands this week, as we take on one of Europe’s most vibrant footballing nations. For many, they reinvented the game, and squad infighting at major tournaments has never been the same since. They are the masters of Total Football. They are the Netherlands.

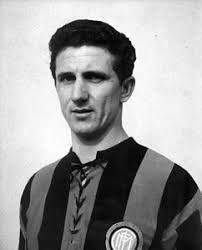

The Player: Faas Wilkes

You might not think it to look at them now, but the Dutch have a rich history of world class forwards. Before Memphis Depay and Ryan Babel there was Robin van Persie and Arjen Robben, before van Persie and Robben there was Ruud van Nistelrooy and Wesley Snjeider, before van Nistelrooy and Sneijder there was Patrick Kluivert and Dennis Bergkamp, before Kluivert and Bergkamp there was Marco van Basten and Ruud Gullit, before van Basten and Gullit there was Johann Cruyff and Johnny Rep, and before Cruyff and Rep there was Faas Wilkes. The Godfather of Dutch Goalscorers.

Wilkes was the Netherlands’ last great superstar of the pre-Total era, a time where the Oranje rarely qualified for the World Cup, and the chances to make a name for himself on the international stage were limited. Born in Rotterdam in 1923 to a working class family, Wilkes’ destiny was to follow in his father’s footsteps as a carpenter until, aged 17, he joined local side Xerxes. Breaking into the first team as a teenager, the young forward’s skill was undeniable. Fleet-footed, and able to outfox defences with his lazy, languid dribbling style, forty-nine goals in four years with the Zebras caught the attention of bigger clubs in both the Netherlands and Europe. KNVB, however, took a dim view of footballers earning a living wage from the sport, and barred the transfer of players both into and out of the country, much to the disappointment of Charlton Athletic and Milan.

Wilkes, though, was single-minded. Desperate to make a living from the game, he sought out a move himself and, after a holiday in Italy in 1949, the inside forward signed his first professional contract with Internazionale. The Dutch Football Federation were incandescent, immediately slapping a five year ban on Wilkes, making him ineligible for national team selection. It was perhaps a desperate grab for authority from the KNVB, but given the explosive goalscoring form that Wilkes has shown in the orange and black of the Dutch side, including four on his debut against Luxembourg, it was very much a case of cutting their ear off to spite their hearing.

In Milan, Wilkes quickly became a fan favourite thanks to his remarkable technical ability. Whilst the San Siro crowds were wowed by his twinkletoes, however, his teammates - and more pertinently his opponents - were less impressed, and the Dutchman found himself the victim of criticism from the former, and the victim of grievous bodily harm from the latter. Two impressive seasons brought third and second placed finishes for Wilkes’ Inter, but injury caused by those trademark bruising tackles from Italian defenders meant that much of his third season was spent on the sidelines. A chance to resurrect his Serie A career arrived with a transfer to Torino, a club still rebuilding following the Superga air disaster. Sadly, time and mistimed tackles had been unkind to Wilkes, and after just twelve appearances and a solitary goal the curtain fell on his Italian adventure.

Three years in Spain with Valencia followed, as the Dutchman rediscovered his form and earned a new set of disciples. Top scorer in both 1953/54 and 1955/56, Wilkes became Valencia’s answer to Di Stefano at Real Madrid and Kubala at Barcelona, helping Los Che to third place in La Liga and a third Copa del Rey victory in 1954. With the KNVB relaxing rules on professional players, Wilkes returned to his native country after three seasons on the Spanish coast, joining VVV Venlo for the inaugural season of the Eredivisie. With his five year ban complete, he was also free to return to the national team, scoring against Saarland on his return.

After two seasons with Venlo, and his career looking like winding down, Wilkes made a surprise return to Valencia, signing with Levante and spending a year banging in the goals in the Segunda Division. Having missed out on promotion, he went back to the Netherlands and led the line for Fortuna Sittard, before ending his career where he started, with Xerxes Rotterdam.

Overshadowed in the history books by the likes of Cruyff and Johan Neeskens, Wilkes was a trailblazer in Dutch football, showing the courage to stand up to the suits at the KNVB, and continuing to play football his way in the face of brutal treatment from the opposition. Having been written off as a hasbeen in his early thirties, Wilkes played on beyond his fortieth birthday and, despite retiring from the game completely once he’d hung up his boots, the forward’s legacy continued. It lived on in Johan Cruyff, the greatest footballer the Netherlands have ever produced, who cited Wilkes as the inspiration for his playing style. It lived on in his goalscoring record, which stood until 1998, when Dennis Bergkamp finally broke it. It continues to live on both at the Sportpark Faas Wilkes where Xerxes play their games, and with the Faas Wilkes Award, handed out to the best footballer in Rotterdam each year.

The Game: West Germany 1-2 Netherlands (1988)

Whilst its a rivalry that has cooled significantly in the last couple of decades thanks to ever expanding globalism, there was a time where the Dutch didn’t much like the Germans. In fact, they bloody hated them with every fibre of their being. Much like all of your Dad’s questionable opinions, it harks back to the war when, on the 10th May 1940 the Luftwaffe invaded the Netherlands, bombarding the country from the air and instigating a battle that lasted four days, and only ended with Dutch surrender following the brutal bombing of Rotterdam. Over two thousand civilians were killed in the attack, which began a five year occupation by the Nazis.

Then there was the 1974 World Cup final, of course. The Dutch had wanted to give their West German counterparts a masterclass on their own patch, taking the lead in the very first minute from the penalty spot, and spending the next twenty minutes just taking the piss out of their hosts. It was a plan that spectacularly backfired, as trademark German efficiency dictated that Franz Beckenbauer and his teammates would ruthlessly dispatch their visitors in the end. Back home, the Netherlands went into mourning, referring to the result as “the mother of all defeats”. It would be another 14 years before they could exact revenge.

The 1980s had been a barren landscape for the Dutch. After back-to-back World Cup final appearances in ’74 and ’78, the post-Cruyff years had seen the Netherlands fail to qualify for ’82 and ’86, missing out on Euro 84 in between. Ahead of Euro 88, being held across the border in West Germany, Rinus Michels returned to the dugout for the third time hoping to go one step further than in 1974. While the Dutch had failed to replace the retiring Neeskens, Cruyff, Rep and Rensenbrink at the end of the seventies, a new generation of slick, skillful footballers cast in the Total Football mould had now emerged, and by the time the tournament rolled around they’d be hitting their peak.

Three players in particular typified the style of football that had made Michels’ Netherlands so popular a decade earlier. Ronald Koeman, a ball-playing centre-back with a penchant for goals, came into the tournament off the back of a spectacular season with PSV Eindhoven, which ended with Koeman lifting three trophies, including the European Cup, scoring twenty-six times in the process. Ahead of Koeman, Frank Rijkaard, a defensive minded midfielder with an exquisite passing range. Not one to shirk tackles, Rijkaard’s ability to play box-to-box was one of his key attributes, seamlessly turning defence into attack with his gut busting runs forward. When there, Rijkaard would find childhood friend Ruud Gullit. Big, strong, fast and powerful, Gullit was perhaps the most technically adept player at Michels’ disposal. Good in the air, two great feet, and able to make a difference from any part of the pitch, the dreadlocked forward was the epitome of Total Football.

Qualification for the tournament was simple. Six wins and two draws saw the Dutch romp home at the top of the group. Once there, things got a little trickier. Defeat in the opening game to the Soviet Union dampened talk of the Netherlands as potential winners, though an out-of-sorts England soon helped increase morale, succumbing to a Marco van Basten hat-trick in Dusseldorf. A late Wim Kieft goal broke Irish hearts in the final group game, but the Oranje rode on to Hamburg, and a semi-final meeting with a familiar foe.

Beckenbauer had swapped the captain’s armband for an ill-fitting suit by now, and had taken an average West Germany side to the World Cup final two years earlier, narrowly missing out to Diego Maradona and Argentina. The new, exciting strike force of Jurgen Klinsmann and Rudi Voller had made light work of Group 1, with only bogey team Italy blemshing the Germans record with a 1-1 draw. For Beckenbauer and his team, victory over the Netherlands was a matter of pride; to be knocked out of their own tournament would be unacceptable, and there was still a shred of ill-feeling from the white side of the divide thanks to the antics of Cruyff and co in ’74.

For the Netherlands, it was more than a game. Thousands of supporters had flocked over the border to create a sea of orange on the Volksparkstadion terraces, and the atmosphere fizzed. Predictably, both national anthems were jeered by opposing fans, preceding a tetchy, tempestuous first half, with plenty of needle and nerves but few signs of quality. Ten minutes after the break, with tempers continuing to bubble, Klinsmann was tripped in the box by Rijkaard. Penalty West Germany. Lothar Matthaus, the pet to Beckenbauer’s teacher, hit a low hard kick into the bottom corner, brushing the fingertips of Hans van Bruekelen. The tension in the German end pricked with a pen; the Dutch, deflated.

Michels’ team stepped up their efforts, both in attack and on the attack. Jan Wouters scythed down the advancing Voller, only for three of the defender’s team-mates to crowd round the permed striker, before Koeman pushed him to the floor. The referee remained non-plussed. Crunching tackles continued to fly in from orange shirts, while Gullit and van Basten were given reign to play at their balletic best. With fifteen minutes to go, Koeman found van Basten in the box. The striker looked to be fairly dispossessed by Jurgen Kohler, but the referee deemed otherwise. Penalty Netherlands. Koeman, of course, stepped up, as he had so often for PSV in the months leading up to the tournament. Another well driven penalty, this time sending the ‘keeper the wrong way. All square, and now the visiting hordes rediscovered their voices.

With the clock ticking towards extra-time, both sides pushed to finish the tie in ninety minutes. Olaf Thon and Pierre Littbarski both went close to winning it for West Germany, before Koeman, again, found Wouters in space. The Ajax man slipped in van Basten, and his outstretched leg guided the ball into the bottom corner, past the despairing reach of Eike Immel. The Netherlands were in the final, revenge had been served, and the Dutch players revelled in it. After the final whistle, having swapped shirts with Thon, Koeman could be seen miming wiping his backside with the German forward’s shirt. File under ‘Things We Say We Don’t Like To See But Actually We Love To See’.

The Netherlands would go on to win the competition in a second meeting with the Soviets, a superb header from Gullit overshadowed by a physics-defying volley from van Basten. For the Dutch, it was the perfect summer. The old enemy vanquished, and a first major trophy to celebrate. Surely now they could put this spat with their neighbours to bed?