On the 29th March 2019, the United Kingdom is (currently) scheduled to exit the European Union. To celebrate forty-six years of peacetime and prosperity in Europe, this season we’ll be profiling the footballing history of each remaining member of the EU, looking at some of their most iconic matches and the players that have left a lasting impression on the game. This week we’re headed to the land that gave us pizza, prosecco and Puccini. They popularised pasta, populated Pompeii and produced Andrea Pirlo, so it seems only fair we pay props to a nation with a culture of romance and a history of barbarism - here’s to Italy.

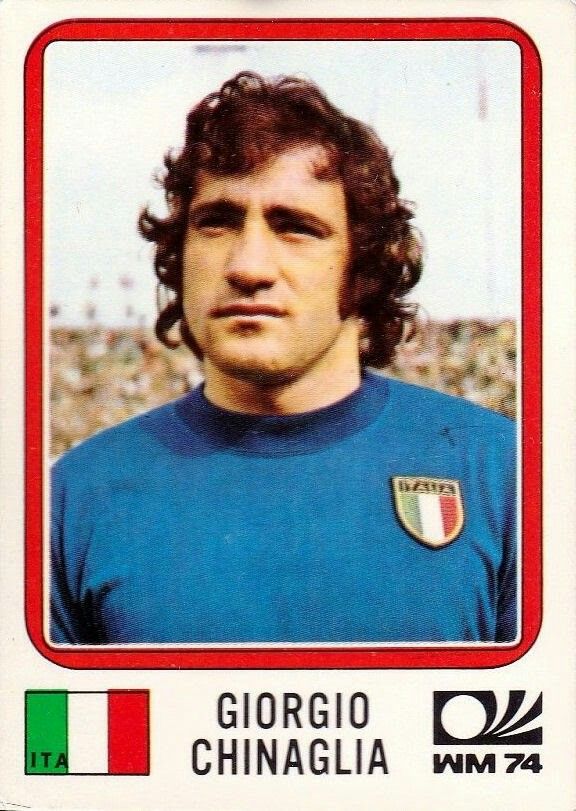

The Player: Giorgio Chinaglia

Italy is a country rich in footballing heroes. From Giuseppe Meazza, Luigi Riva and Gianni Rivera, to Roberto Baggio, Paolo Rossi and, for a few weeks at least, Toto Schillaci; and that’s just the attacking players. It’s almost perverse that, when paying tribute to Italy’s contribution to world football, we should pick a striker when the identity of the national team is so keenly associated with defensive play, but Giorgio Chinaglia’s tale is too good to ignore. Born into the poverty of post-war Italy in 1947, Chinaglia’s family decamped to south Wales in the mid-fifties, cramming themselves into a single room in a shared Cardiff house, living off his father’s measly ironworker’s wage. Within twenty years he would be a Capocannoniere.

That childhood deprivation stood the youngster in good stead when it came to applying himself on a football pitch. At thirteen he was spotted playing for Cardiff Schools, and offered an apprenticeship at Swansea Town (known today as Swansea City). At the age of seventeen, he made his debut for the Swans in the old Third Division, scoring the only goal of his career at the Vetch Field against Bournemouth in August 1965. His time in South Wales was cut short by a call from the Italian military, and his family moved home to allow Chinaglia to complete his national service. Having already earned himself a reputation as hard-drinking party boy in Britain, his time with the military gave the young striker a chance to work on his fitness, spending most of his days training, and being released to play matches for Serie C side Massese.

His spell in the English professional leagues meant he was forbidden for turning out in Serie A for his first three years back in Italy, a circumstance that Massese, and a year later Internapoli, benefited from immensely. During his time in the third division, Chinaglia showed he was a class above his contemporaries, averaging a goal every three games despite being in his early twenties. That run of form, combined with the end of his top-flight ban, led to Lazio taking the plunge and signing the young striker. Twenty-one goals in his first two seasons at the Stadio Olimpico weren’t enough to prevent The Eagles’ relegation to Serie B in his second year at the club, but it was their promotion campaign the following season that saw the striker come of age.

After his twenty-one goals helped Lazio return to the top flight as runners-up, Chinaglia and his team narrowly missed out on their first scudetto the following season to Juventus. In 1973/74, however, that elusive title would arrive in Rome, as the striker dubbed ‘Long John’ by Lazio’s supporters embarked on a one man mission to win the league, racking up twenty-four goals, including the championship winning penalty against Foggia. His place in Lazio folklore secured, Chinaglia stayed just one more year, taking his tally in white and sky blue to ninety-eight goals

By now, despite hitting his prime, the striker’s international career was over. A foul-mouthed tirade aimed at national team coach Ferruccio Valcareggi following his substitution in the opening game of the 1974 World Cup against Haiti had soured relations between the player and the Italian Football Federation, and though he managed to pick up caps under Valcareggi’s successor Fulvio Bernardini, his playing style and attitude was not considered conducive to a successful Italian team.

With international concerns off the agenda, Chinaglia’s next move was a bolt from the blue. Having enjoyed seven successful seasons with Lazio, the maverick striker then packed his bags and headed for New York Cosmos in the North American Soccer League, joining up with Pele and Franz Beckenbauer, both advancing in years and taking advantage of the financial benefits the American market had to offer. There was no doubt that Chinaglia’s decision to join a league so low on prestige was purely financial. He had already begun investing in American real estate while at Lazio, and had grown tired of Italian tax laws and corporate red tape. Whilst never the most skilfull or technically proficient player, Chinaglia’s talent clearly shone through at Cosmos, as he racked up an incredible 193 goals in 213 appearances in New York, setting records for most goals in a NASL season with 34, and most goals in a NASL indoor match with seven. By 1984, with the NASL crumbling under financial pressures, Chinaglia was handed sixty percent of the clubs ownership, with his personal assistant retaining the rights to New York Cosmos upon the club’s dissolution in 1986.

After a brief stint at Lazio president in the mid-eighties, an attempt to purchase the club in 2006 was aborted after interference from the Italian authorities, who wished to question Chinaglia on accusations of money laundering. A similar bid for Foggia two years earlier had led to the Tuscan returning to America, where he saw out his final years as a co-host on Sirius Radio’s daily football show. In 2012, at the age of 65, Giorgio Chinaglia died of a heart attack.

Though peppered with age-old tropes of corruption and greed, Chinaglia’s life and career should perhaps be viewed through the lens of a young immigrant who harnessed the limited ability he had to carve out a respectable career at the top level of football. His bravery on the pitch, desire to score at any cost, and dedication to provide the best possible life for his family has the makings of a classic rags-to-riches fairytale. The fact he did it all while partying hard, putting Pele in his place, and sticking two fingers up to the establishment makes his legacy all the more laudable.

The Game: Germany 0-2 Italy, 2006

It’s fair to say that Italy and Germany have some history. There’s even a plaque embedded in the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City to commemorate the two nations’ involvement in The Game of The Century, that barmy 4-3 win for the Italians in the 1970 World Cup semi-final. Twelve years later, the two sides met again, this time in the final in Spain, and once again in was the boys in blue that emerged victorious. In fact, only England have beaten Germany on more occasions than Italy, and ahead of their meeting in the 2006 World Cup semi-final, the Azzurri had never lost a competitive match against Die Mannschaft.

It was surprising to many that either team had even made it this deep into the tournament. Ahead of Germany’s first time hosting of a tournament as a united nation, home supporters were afraid of being utterly embarrassed by their national team. Though they’d finished runners-up four years previously, the luck of the draw had seen them reach the final, and they were completely outclassed by Ronaldo and Brazil. At the Euros two years later, they were dumped out of the group stage by the Czech Republic, having managed just a goalless draw against rookies Latvia. The introduction of Jurgen Klinsmann as national team manager and Oliver Bierhoff as general manager, as well as an overhaul of youth football in the country, had brought new hope, and from the moment Philip Lahm had cracked in the opening goal of the 2006 World Cup against Costa Rica, the hosts were up and running, seeing off old enemy Argentina in the quarter-finals to set up a meeting in Dortmund with Italy.

The Italians, meanwhile, had endured a typically slow start. A draw against the United States in their second game had provided an early wobble for Marcelo Lippi, but a comprehensive victory over the Czech’s saw them finish top of the group. What followed was an unerringly straightforward route to the last four, with a resolute Australia undone by a dodgy last minute penalty, before Ukraine were swept aside. After exiting Euro 2004 at the group stage, and their shock defeat to South Korea in 2002, the serenity of Italy’s tournament was a foreign concept.

Lippi had been parachuted in following the debacle in Portugal, with Giovanni Trappatoni vacating the role in disgrace. The Tuscan had most recently returned Juventus to the top of Serie A in his second spell in Turin, adding two more scudettos to his ever-growing list of honours that include The Old Lady’s most recent European Cup triumph. A straightforward qualifying campaign, beaten just once in ten matches, had seen the emergence of Palermo’s 29 year old striker Luca Toni. Having scored twenty goals in the Rosanero’s return to Serie A, Toni earned himself a move to Fiorentina and, in the year leading up to the World Cup, earned the Capocannoniere title with thirty-goals for the Viola. His inclusion in Lippi’s squad was a no-brainer.

Toni was joined by a cast of seasoned internationals, with Lippi naming sixteen players aged 28 or above in his squad, with only five having earned fewer than fifteen caps. Among those familiar faces were Gigi Buffon, Fabio Cannavaro, Alessandro Nesta, Francesco Totti and Alessandro Del Piero, an impressive spine with 352 appearances for the Azzuri between them. That experience would prove vital against a youthful Germany team desperate to win the trophy in front of their own fans.

Italy’s tournament had been played out amidst the noise of the Calciopoli scandal, as Juventus, Milan, Fiorentina, Lazio and Reggina were implicated in match-fixing allegations that would see Juve relegated to Serie B for the 2006/07 season. Fourteen of Lippi’s squad had been playing for the accused in the lead up to the tournament, and whilst the crimes had been committed at boardroom level, predominantly by Juventus general manager Luciano Moggi, the media circus that surrounded the scandal undoubtedly had an effect on the players. That the likes of Cannavaro and Buffon were able to maintain focus on the tournament whilst their domestic situation deteriorated on the front-pages of the national newspapers was a testament to their professionalism.

The game itself was a classic slugfest between two of football’s most storied nations. Italy did what Italy do best and soaked up pressure from the hosts, with Cannavaro in particular in gladiatorial form. As the game wore on, perhaps keenly aware of the opposition’s ruthless efficiency from the penalty spot, the Italians began to assert themselves, with Lippi throwing on attacker after attacker in a bid to win the game within ninety minutes. Buffon’s smart saves from Miroslav Klose and Lukas Podolski had kept the scores level, and at full-time neither side had been able to find a winner.

The introduction of Del Piero on the stroke of half-time in extra time pulled the momentum back in Italy’s favour, with the wily Juventus forward causing problems for Germany’s stoic yet immobile backline. With the clock showing 119 minutes, Del Piero played a quick short corner to Andrea Pirlo on the edge of the box, and the Milan playmaker’s exquisite reverse pass found the path of full-back Fabio Grosso. With one look, Grosso curled his effort round the despairing reach of Jens Lehmann to break German hearts. The goalscorer, in the white heat of the moment, embarked on a celebration that recalled Marco Tardelli’s ecstatic sprint following his goal against the same opponents in 1982. In the final seconds, with Germany pushing forward for an equaliser, Cannavaro’s interception found its way to Alberto Gilardino who, feigning to cut inside, slipped in Del Piero to add the icing on a champions performance. Italy were through to meet France in Berlin, while the hosts could look back on a tournament that had exceeded expectations.

Italy would go on to beat France in the final in a tense and tortured affair best remembered for Zinedine Zidane’s moment of head-loss. Cannavaro would go on to win the Ballon D’or for his performances in Germany, in particular that colossal showing against the hosts. Since that World Cup win, the Azzuri have fallen back into the doldrums, failing to qualify for the World Cup in 2018, but the memories of Dortmund, where they tore Germany apart, still live on.